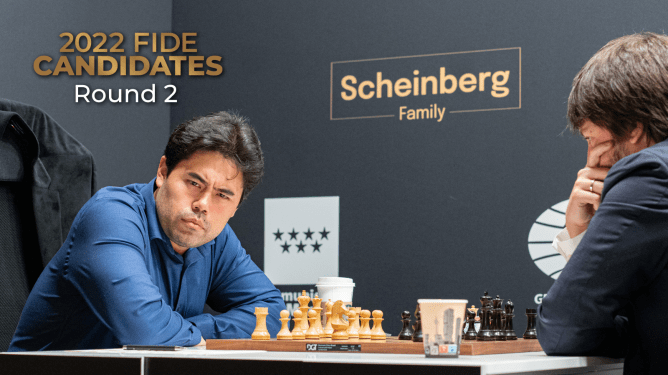

GM Hikaru Nakamura came back strongly in the second round of the 2022 Candidates Tournament. The American grandmaster ground down GM Teimour Radjabov in an endgame to score the full point, with the other three games ending in draws.

After the very exciting first round of this Candidates Tournament, things slowed down a bit in the second round but not much. Both opening theoreticians and endgame lovers had their reasons to enjoy their Saturday, with once again lots of fighting chess.

In both the Nepomniachtchi-Caruana and Duda-Ding clashes, the middlegame position was still full of life when the games suddenly finished in a draw by move repetition. In such a high-profile tournament and especially early on, it’s not uncommon that players switch to safety mode.

Firouzja had to work hard on his 19th birthday to eventually escape with a draw in his second black game in the tournament. At the end of the day, six and a half hours into the round, Radjabov threw in the towel against Nakamura. As a result, nobody has a perfect score anymore, while nobody is on zero points either.

Nepomniachtchi-Caruana ½-½

The only two players in history who did start a Candidates Tournament with a perfect 2/2 were GM Max Euwe in 1953 and GM Tigran Petrosian in 1959. (Neither of them ended up winning the tournament.) Nepomniachtchi and Caruana seemed to be trying hard to do something about that statistic, but in the end, they settled for a peaceful outcome.

The two top GMs, who happened to be GM Magnus Carlsen‘s last two opponents in the world championship, had also drawn nine out of their 10 previous classical games, including both games in the previous Candidates. It was in 2019 in Zagreb, Croatia where Nepomniachtchi managed to score the full point.

Although they drew today, the theoretical battle in this Italian game was clearly won by Caruana. He played his first 16 moves in just six minutes, while his opponent had already spent an hour by that point.

The American’s choice of 9…g5 was perhaps slightly surprising as current theory doesn’t rate it too high. In an online course, top GM Anish Giri commented about the move:

“This was very trendy for a while, with even Magnus Carlsen trying it when there was still surprise value to it. By now, I believe it is more or less clear how this aggressive push should be dealt with.”

Giri, however, didn’t mention 10…Ng4. This move, a novelty, turned out to be part of a remarkably risky strategy by Caruana.

Caruana revealed afterward: “I knew that 10…Ng4 would come as a surprise. I don’t know if many people have analyzed this move. 10…Ng4 is borderline losing, it was a huge gamble. It’s not losing, it’s probably not even very bad, but it’s definitely a very dubious move but I was kind of counting on the surprise factor.”

Commentator GM Jon Ludvig Hammer was impressed by Nepomniachtchi’s decision to go for the pawn sacrifice 15.d4, saying: “He had to build the courage to really put the pressure on Black in a position where he had to assume that he was still in Caruana’s home preparation.”

It was the first moment Caruana needed to check himself; he spent 1.5 minutes before taking on d4. Two moves later, the 2018 winner was finally on his own: “He shocked me with this 17.Ra3 move, I didn’t see that one coming.”

As the position got sharper, it felt like both players could be playing for a win, with Caruana a pawn up and Nepomniachtchi with two potentially very strong bishops.

Commentator IM Almira Skripchenko also liked how Nepo handled himself, saying after he had played 26.Qd1: “We are completely obsessed during our games with concrete variations but maintaining the pressure on the board is very important. He is not going for a concrete line, but increases the pressure.”

The game got all the more interesting when it appeared that Black had the possibility of an exchange sacrifice on b2, but instead, the players repeated moves and Caruana claimed a draw before making his intended 31…Rg8.

“I thought my position was very good, at some point I thought I was much better but I couldn’t find a way to exactly coordinate my pieces,” he said.

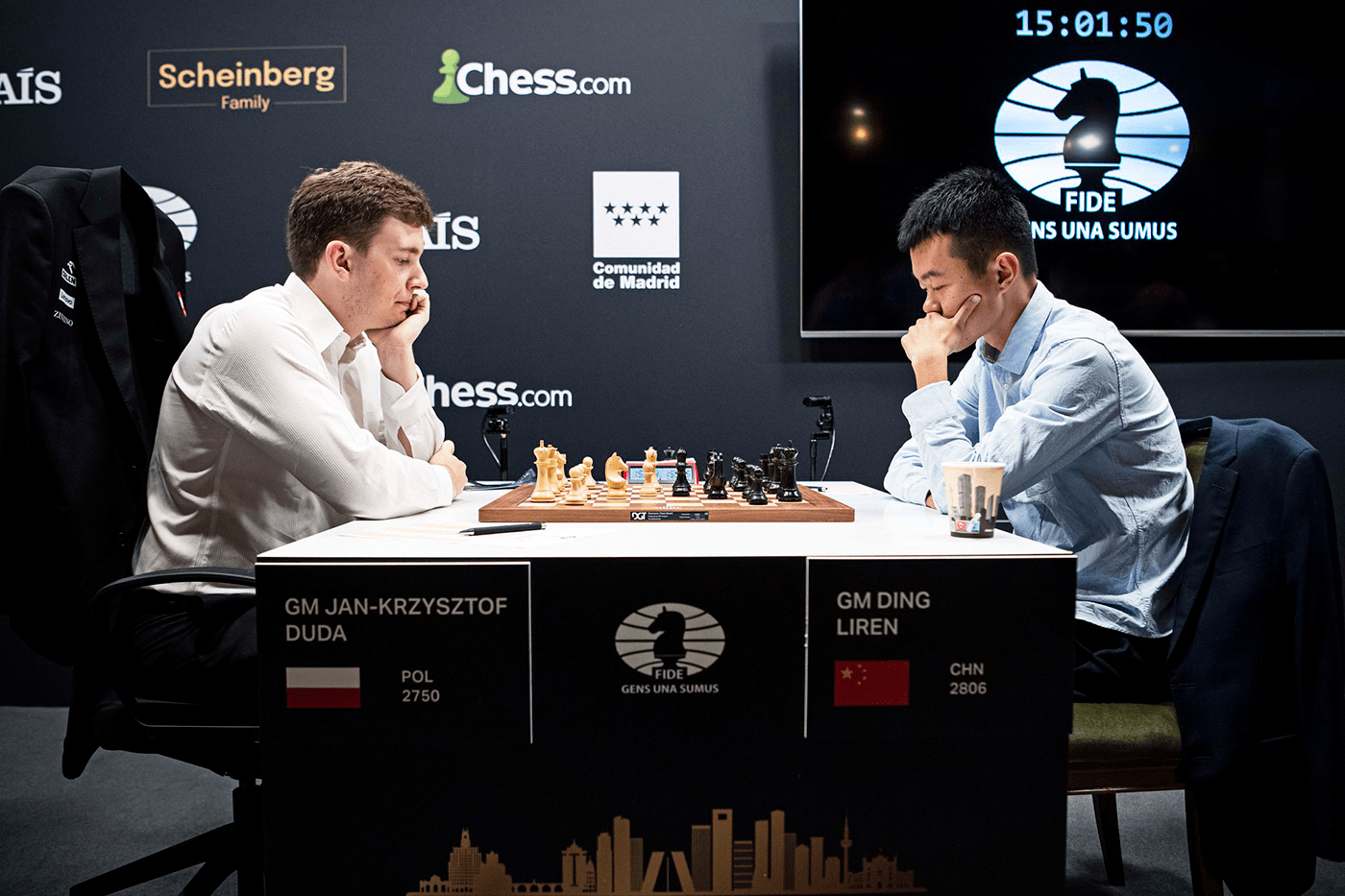

While he lost both his first and second game in the Candidates in 2020, Ding dealt with his round-one loss much better this time around. Perhaps helped by the switch of chairs (preferring a more regular size than the large office chairs that were arranged for the players), Ding was looking like good old Ding today.

Playing his solid 1…e5 repertoire and coming up with some nice queen maneuvers, in what was another Italian game, he avoided any trouble and was even slightly by move 20 better according to the engine. Ding thought so too.

The world number two suddenly went for some aggression with 23….g5, a move he faced himself yesterday.

“It looks like my move 23…g5 is not so good, but I don’t know where I went wrong,” said Ding afterward, but the move might have had the psychological effect that Duda overestimated Black’s position a bit. In the final position, Ding actually liked White a bit more.

But also here, somewhat unexpectedly the game ended in a threefold. Duda repeated moves, which Ding had no reason to reject. He stopped the bleeding as early as round two, unlike two years ago.

“I’m not very satisfied with this game, to be honest,” admitted Duda afterward. “I prepared an idea in the opening which of course didn’t give me any objective advantage, but I hoped to get a playable position and outplay him somehow. The thing was that I wasn’t feeling very comfortable in this position. I basically didn’t know what to do!”

Duda agreed that, if anyone, it was his opponent who had the better chances, so he was content with the draw. “I missed a lot of stuff in this game. He played some moves I wouldn’t have found in a million years!”

You could say that Rapport gave Firouzja a birthday present in this game, by not winning a won position. In fact, that might have happened twice.

Staying true to his common strategy of playing off-beat openings, Rapport chose the 4.Qxd4 line of the Sicilian, to which Firouzja’s 5…a6 wasn’t the most popular choice either. The surprise effect?

By move nine, there were some remarkable similarities with Rapport’s game of yesterday: this time it was the Hungarian player who went for the Maroczy Bind setup against a Sicilian, facing a king’s knight going to e7 and then also the early c4-c5 push.

It led to the same pawn structure as in the Duda-Rapport game with the isolated pawn on c6 for Black, who seemed to have a better version as it was easy to protect it with harmonious piece play. Nonetheless, Rapport managed to keep a slight edge until a double rook endgame was reached shortly before the time control.

Whereas he had done a good job defending his pawn-down rook endgame the other day, this time Firouzja went astray right away, choosing the wrong plan. Often, it’s important to play for activity in rook endgames, but giving up that ever-so-weak c6-pawn so quickly in order to create counterplay on the kingside (32…Ra1, 33…Rh1) was too dangerous because of another well-known theme: the double rooks on the seventh rank.

Rapport got a winning position but seems to have chosen an inaccurate continuation with 38.Ke4, a move he spent only 40 seconds on while having 15 minutes on the clock. (Firouzja was making his last few moves with about a minute on the clock.)

When the time control was reached, Rapport had an extra hour to try and find the winning line and after spending 25 minutes he went for 41.Kf4. The engine was showing a winning advantage indeed, but the lines it provided didn’t too convincing. Was it a case of horizon effect?

In any case, it was too difficult for a human to understand, let alone calculate. The game soon was heading for a draw, although on one more moment, the eval bar jumped up for White. A long line starting with 52.Kf5 eventually leads to a winning tablebase position on move 61, go figure!

Since 2011, the two oldest participants in the field had played 14 times before, with two wins for Naka and no losses. Those two wins had come against Sicilians, but this time the Azeri GM played the solid 1…e5. It didn’t help.

As it went, Nakamura was looking at another Berlin Ruy Lopez, this time from the white side. Unlike Caruana the other day, he did not the knight on c6 with his bishop—the main line these days—but chose a line where White does not give up the bishop pair. Radjabov was definitely surprised and at some point, he was down almost an hour on the clock.

It was time well spent, though, because Radjabov was very close to fully equalizing by move 17. That probably dawned on Nakamura, who spent 32 minutes on his 18th move and another 19 on the next, when his edge on the clock had completely vanished.

He had found a good solution though, trading the dangerous b6-bishop off for the so far undeveloped counterpart on c1.

According to the engine, Black was fine for a while as Nakamura chose the committal 21.d6 over 21.Rd1, but Radjabov’s lack of time did start to play a role. He had 54 seconds for his last three moves to the time control and 15 seconds to make his 40th, which he made with two seconds left. Note that in this tournament, the players only get their 30-second increment after move 60.

“Hikaru’s advantage seems to have increased against Radjabov after the time scramble,” said IM Danny Rensch. Materially, that was the case as well. Nakamura had won a pawn, was left with good winning chances, and succeeded wonderfully in converting it.